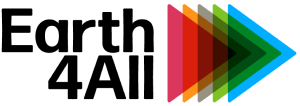

Planetary Stewards are a major political grouping in the world’s most powerful countries. One in five people could be considered Planetary Stewards. On top of that Concerned Optimists and Steady Progressives both support widespread action for long-term stewardship of Earth. Together these three groups make up 61% of G20 citizens.

As the planetary emergency becomes acute, it is increasingly important to understand people’s beliefs and attitudes to planetary stewardship. Planetary stewardship is more than just a narrow belief that humans are causing the climate to change. In the Anthropocene, it has to be a commitment to greater political and economic change to stabilise Earth.

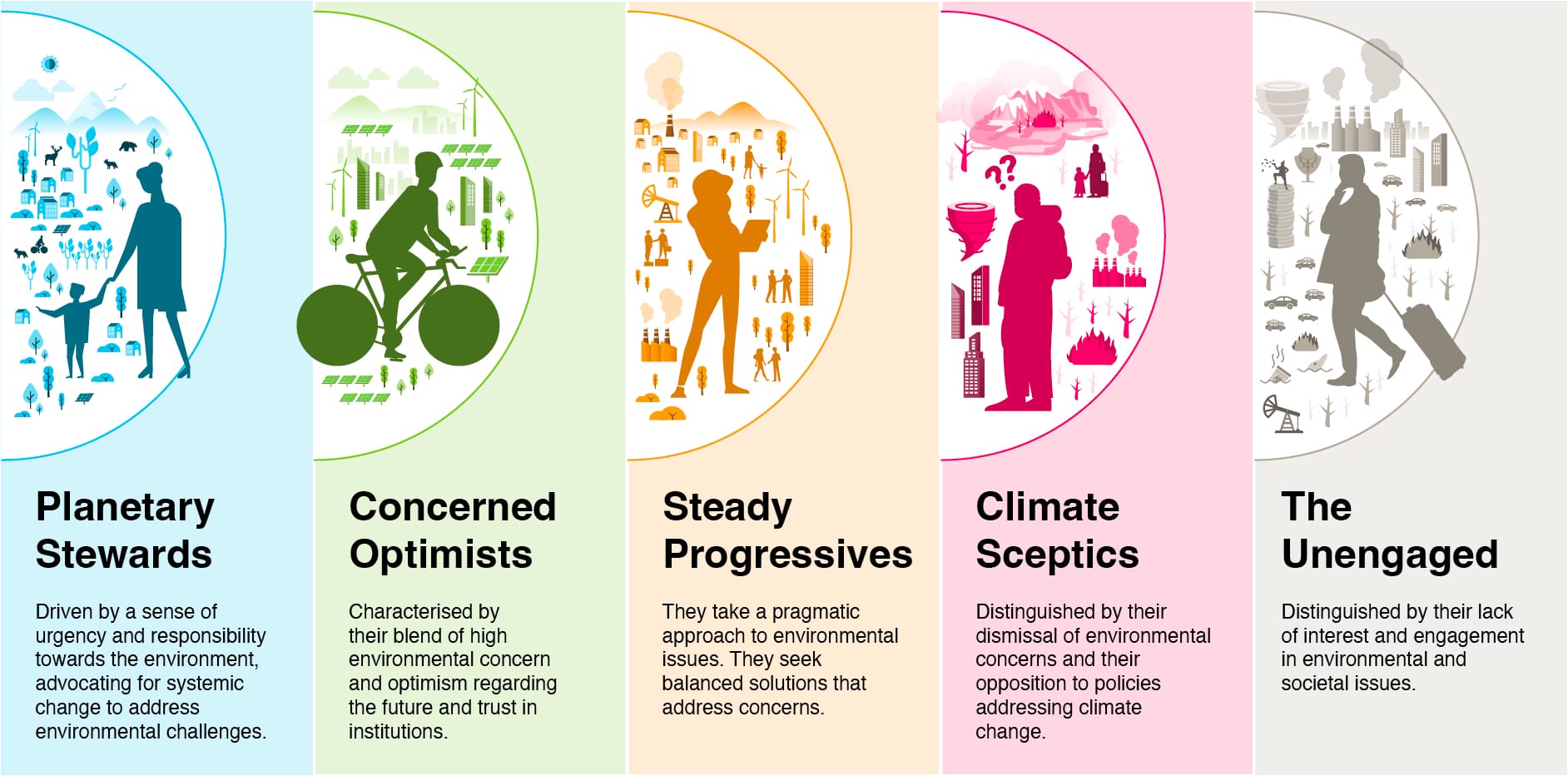

In the last nine months, Earth4All and the Global Commons Alliance have been running a project to explore attitudes to planetary stewardship. We commissioned Ipsos to conduct a global survey of G20 countries (minus Russia for obvious reasons). We chose the G20 because these countries represent about two-thirds of the global population, around 85% of the global GDP, 78% of greenhouse gas emissions and over 75% of the global trade.

We were particularly interested in segmenting audiences within the G20 countries into distinct “planetary steward segments.” Why is market segmentation important? Market segmentation is a powerful tool for political and advocacy groups to ensure their efforts are focused, relevant, and impactful, leading to more effective campaigns. It can help target messages to specific yet large audiences, it can help prioritise issues that matter to people and it can be used for strategic advocacy.

We wanted to segment the G20 audience to explore the scale of support for stewardship and to see if we could identify different archetypes. Who are the planetary stewards of this world? Who are the people who dismiss the notion of planetary stewardship? Might they also distrust government more generally?

The analysis led to the identification of five distinct planetary stewardship segments that provide a nuanced view of how different groups perceive and engage with the challenges of planetary stewardship. The findings reveal that a significant majority of people in G20 countries – a full 61% – support widespread action to protect and stabilise the planet. Conversely, hardline sceptics who deny much action is required make up a paltry 13% of people. Around one quarter of people (26%) remain unengaged in political issues generally, and environmental issues in particular.

Five distinct “planetary steward segments” among the G20 audiences:

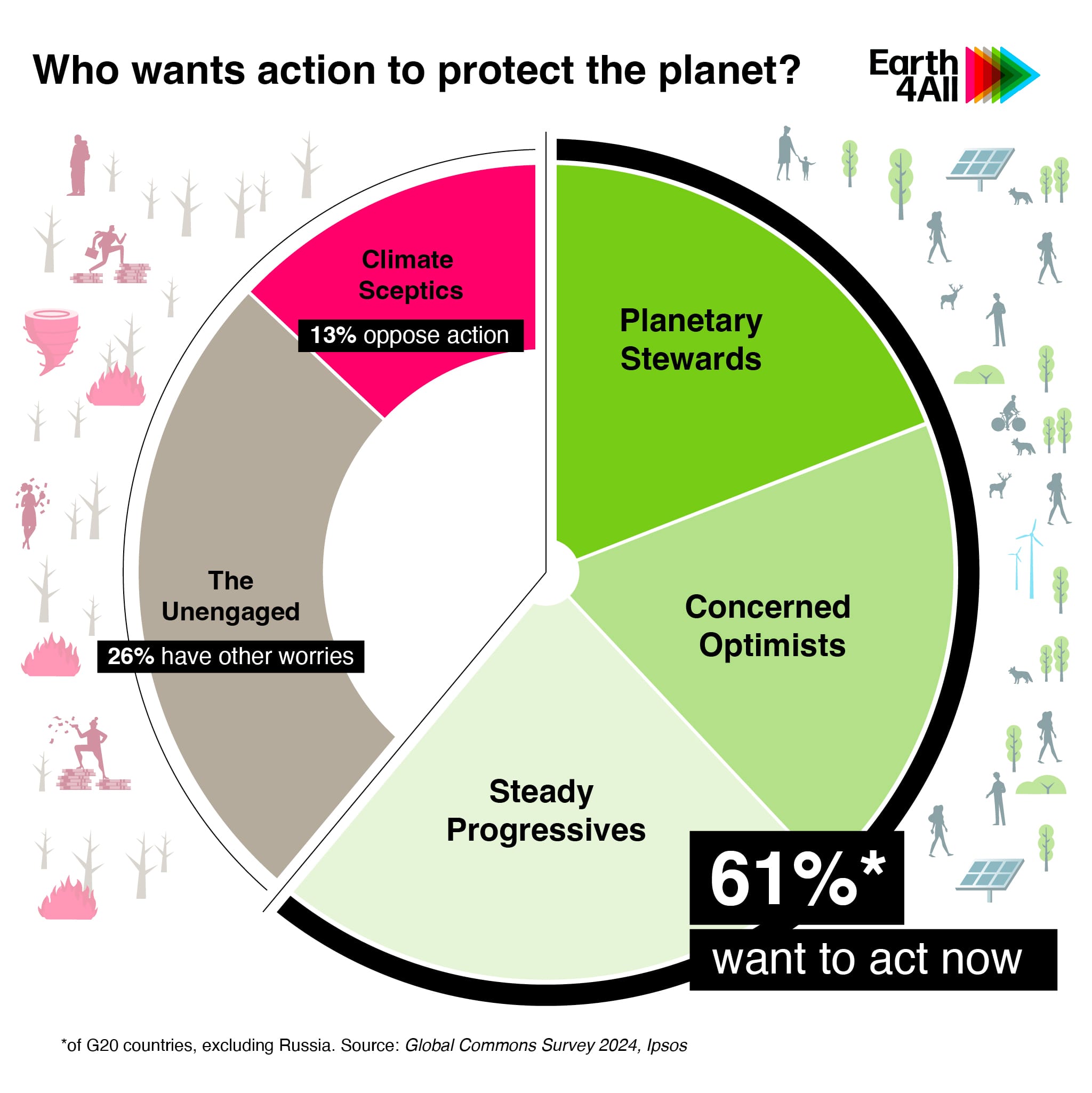

1. Planetary Stewards (19% of G20): This group is characterised by a strong sense of urgency and responsibility towards environmental issues. They advocate for systemic change and believe that immediate action is necessary to address the pressing challenges facing the planet.

2. Concerned Optimists (19%): These individuals are deeply concerned about environmental issues however remain more optimistic about the future than our planetary stewards. They support wide-ranging, rapid action but trust that institutions and technological advancements will play a key role in solving environmental problems.

3. Steady Progressives (23%): Pragmatic and moderate, Steady Progressives seek balanced solutions to environmental challenges. They show deep concern about the state of the planet but generally advocate for gradual reforms within existing systems to achieve sustainability and are less likely to see the need for a complete reform of economic and political systems.

4. Climate Sceptics (13%): Representing a small but vocal minority, Climate Sceptics dismiss the severity of environmental issues and oppose policies aimed at addressing climate change. They are less likely to feel personally exposed to environmental risks.

5. The Unengaged (26%): This group is characterised by a lack of interest and engagement in environmental and societal issues. They are less likely to support urgent action and often exhibit a low level of political and social involvement.

The basis of the segmentation was people’s responses to 12 statements within the extensive Ipsos survey:

- Concern for the state of nature today.

- Concern for the state in which we will leave nature for future generations.

- Because of human activities, the Earth is close to environmental ‘tipping points’ where climate or nature, such as rainforests or glaciers, may change suddenly or be more difficult to stabilise in the future

- New technologies can solve environmental problems without individuals having to make big changes in their lives.

- Many of the claims about environmental threats are exaggerated.

- Human health and wellbeing are closely connected to the health and wellbeing of nature.

- Nature can meet the needs of humans right now.

- Nature is already too damaged to continue meeting humans’ needs in the long-term.

- Addressing climate change and environmental damage can bring many benefits to people in <Country>.

- <Country> government is doing enough to tackle climate change and environmental damage.

- The costs of the damages due to environmental pollution are much higher than the costs of the investments.

- It should be a criminal offence for leaders of large businesses or senior government officials to approve or permit actions they know are likely to cause damage to nature and climate.

Ipsos’s preferred approach for segmentation is to use ‘ensemble’ clustering techniques. Rather than running a cluster analysis once, ensemble techniques run many possible solutions that, through an iterative process, converge on a solution that is highly stable and reproducible. The sample size of 1000 people per country allowed for this. On account of the very broad nature of the survey, which includes many questions relating to attitudes to democracy, political reform and economic security, we were able to develop quite detailed personas that may help us understand people’s complex relationship with the environment. For example, if so many people support greater planetary stewardship, why are populist movements, that often dismiss climate concerns, on the rise? Certainly, climate sceptics generally distrust government and believe in smaller government. They may worry that responding to climate change will mean government over-reach making them uncomfortable. One curiosity within this data is that both Planetary Stewards and Climate Sceptics share a common distrust in government. One might even suggest that Ronald Reagan was correct in saying “government is the problem.” The solution, though, may not be smaller government, but rebuilding trust in government.

The global implications of the Planetary Stewardship Personas

Our findings highlight the growing global consensus on the need for urgent environmental action. Planetary Stewards are a major political grouping in the most powerful countries in the world. One in five people could be considered Planetary Stewards. On top of that Concerned Optimists and Steady Progressives both support widespread action. Together these three groups make up 61% of G20 citizens. There is a clear mandate for governments and institutions to step up their efforts. While the European Union, the US, UK and elsewhere have implemented ambitious policies in line with citizen support in recent years, aggressive political opposition is attempting to weaken support. Our results show this is not aligned with citizen opinion on these issues where just 13% of people fiercely oppose planetary stewardship. However, the presence of a large unengaged minority highlights the need for targeted communication and engagement strategies to mobilise this group.

Understanding the distinct segments within the G20 audiences can help policymakers, NGOs, and businesses tailor their communications approaches to resonate with different segments of the population. By recognizing the different motivations, concerns, and levels of engagement among the global population, we can develop more effective strategies to ensure a sustainable future for all.

Comparing results with Yale’s Global Warming’s Six Americas

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication regularly releases survey results related to its “Global Warming’s Six Americas” framework. In 2023, based on this framework, Yale published data from a survey of Facebook users in nearly 200 countries and territories using four simple questions to segment the audience:

- How important is the issue of global warming to you personally?

- How worried are you about global warming?

- How much do you think global warming will harm you personally?

- How much do you think global warming will harm future generations of people?

The new Planetary Stewardship segmentation provides a useful complement to the “Six Americas” approach. While both studies report high levels of concern about climate change, the Planetary Stewardship analysis goes further than climate change to explore broader attitudes to the state of the planet. Both studies observed higher levels of concern in lower- and middle-income countries compared to high-income nations. The Planetary Stewardship study provides additional insights on trust in government, economic attitudes, and support for systemic changes.

The segmentation results are part of the 2024 Global Commons Survey which focuses on attitudes to the state of the planet. In June 2024, we published the complementary Earth for All Survey which explores attitudes to economic and political change. Data for both surveys were collected by Ipsos in April 2024.