In this Q&A, philosopher and author Roman Krznaric talks about the importance of long-term thinking and our responsibility towards future generations.

Why is long-term thinking important?

My work is centred around a question: ‘How can we be good ancestors?’. Back in the 1970s when the The Limits to Growth was published, the immunologist Jonas Salk raised big questions about the long-term future of human civilisation, and how we will be judged by the generations to come for what we have and haven’t done. It’s a question that, of course, has been central to the thinking of indigenous communities worldwide and their visions of ecological stewardship. My work is centred around this theme – it’s about long-term thinking.

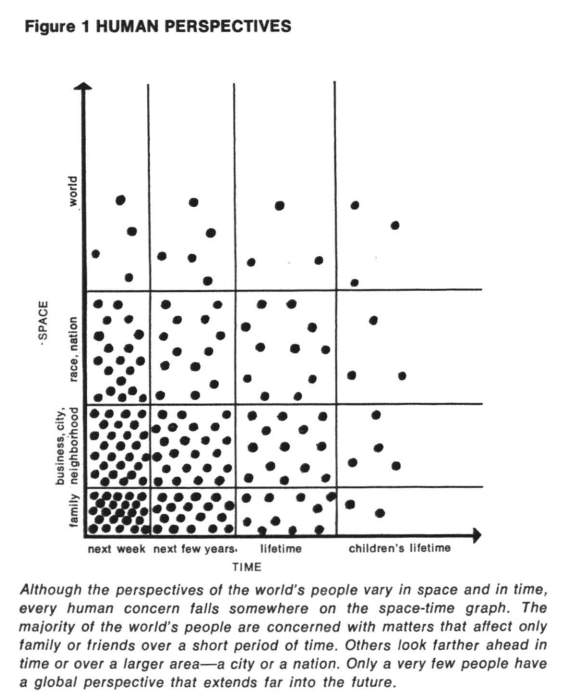

In The Limits to Growth, there is a graph (see below) about human perspectives – and that is what it’s about: how do we think beyond our own lifetime? And what implications does it have for economics, politics, and culture?

How does short-termism impact the economy?

Our economic systems and ideologies have made us blind to the future, and ecological impacts are currently an afterthought.

We have to rethink what economics is at its core. It doesn’t make sense to have an economy where you’re using resources faster than they can naturally replenish, or create more waste than can be naturally absorbed in oceans and other carbon sinks.

In practice, to think long-term, you don’t need to project 100 or 300 years ahead, but we do need to live within the boundaries of our planet. We have the imaginative capacity to think about the young people in our lives, such as our children, nephews, or nieces, and that means thinking about all lives. It means thinking about the water they will drink and the air they’ll breathe, and since everyone breathes the same air, it means taking care of everybody’s air. In this way, something personal can be a bridge to something more universal, a care for the universal strangers of the future and the planet they live on. Humans are multi-generational creatures, throughout our lives we may meet 5 different generations. In ways, that is what the span of the report The Limits to Growth was covering: 100 years in the past and 100 years in the future. And that is exactly the thinking we need today.

It is important to recognise that we need to change our political structures – which is already happening in many places. Wales, for example, has a Future Generations Commissioner, who looks at the impact of public policy up to 30 years ahead. The UK are considering something similar and Finland has a parliamentary committee for the Future.

Why did you join the Earth4All Transformational Economics Commission?

We are at a stage where never before in human history have our actions had such damaging impact for future generations. In the Earth4All project we think beyond the here-and-now to consider the trajectory of human civilisation.

Earth4All is also trying to change public policy and to get politicians and officials to consider the urgency of issues beyond the next couple of years. It asks questions like: What are we trying to do? How do we recognise the colonial legacies and ensure that the responsibility of the historically big-carbon emitting Global North is accounted for? And ultimately: How can we be good ancestors?

Fifty years ago, the report The Limits to Growth was already highlighting the need to look a hundred years in the future. What has changed since then?

When The Limits to Growth came out, it sparked a lot of public conversation and controversy. Today, the availability of data changes and the strength of forecast is much stronger. We know, within margins of errors, that by following Business-as-usual we will be hitting 3 to 4 degrees of heating and 1 to 2 meters of sea level rises by 2100.

It is also clear that the neoliberal dream has not delivered. An economics which doesn’t account for the planet cannot preserve the one planet we know that sustains life. Neoliberalism is dying. Students are walking out of their classes, not wanting to be taught an economics that has nothing to do with the planet, and that has no inherent pluralism.

I don’t believe that fundamental and rapid social change happens without disruption from below – like the work of Fridays for the Future, Extinction Rebellion, the Sunrise Movement and all the activist movements. They play a fundamental role in changing the nature of the public conversation. It is a sign of hope. I know it annoys people, I know it’s disruptive. But it’s less disruptive than living in a world heading towards three to four degrees heating. Creating change is about that kind of disruption.

What’s our responsibility towards future generation?

I believe we have colonised the future. Especially in the Global North, we treat the future as a dumping ground for ecological degradation and technological risks, as if there was nobody there. That is a violation of the rights of future generations, particularly those living in the Global South who will experience (and are already experiencing) this impacts of this colonisation. We need an anticolonial struggle, just like there have against the traditional colonisation of land. We need to bring the voice of future generations in the room when we are having discussions, by inviting young people onto the boards of companies, through citizen assemblies, or by giving rights to future generations.

Is there a good example of an existing way to represent future generations in decision-making?

In Japan, a movement called Future Design is directly inspired from the Native American idea of 7th generation decision-making. Future Design invites local people to discuss and plan for the town where they live. Participants are divided into two groups: one is told they represent residents from the present day, and the other half are given ceremonial robes to wear – they have to imagine themselves as residents from 2060. The evidence shows that the 2060 residents systematically think more long-term, and make more radical transformative decisions.

This movement is spreading across Japan and is used in small and big cities like Kyoto, companies like Fujitsu, and even Japan’s Ministry of Finance. It’s also spreading internationally.

This is just one example, that takes a citizen assembly and adds an incentive to imagine the future. And that long-term dimension makes it so much more powerful.

Roman Krznaric is a philosopher and author, writing about the power of ideas to change society. He is a Research Fellow at the Long Now Foundation, and founded the Empathy Museum.

Further Resources:

Roman Krznaric’s website: https://www.romankrznaric.com/

The Good Ancestor: how to think long term in a short term world (Roman Krznaric, 2021)

‘How to be a good ancestor’, Roman Krznaric, TED Talk (2020).