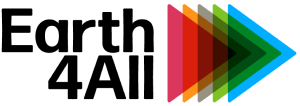

The release of the new EAT-Lancet report on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems once more highlights a stark reality: agriculture is now the main driver of multiple planetary boundary transgressions. From soil degradation and biodiversity loss to freshwater use and greenhouse gas emissions, our food system is pushing Earth far beyond safe limits. If we want a stable planet and healthy communities, agriculture must make a turnaround and transform—fast.

But agriculture holds a unique position in the global sustainability challenge. It shapes not only the food on our plates but also the ecosystems that stabilise the climate and are key to Earth resilience. Changes on farms can ripple outward, regenerating soils, landscapes and even elements of the Earth system itself. Yet despite its centrality, our understanding of how large-scale shifts to regenerative agriculture actually happen—and what drives or blocks them—remains limited.

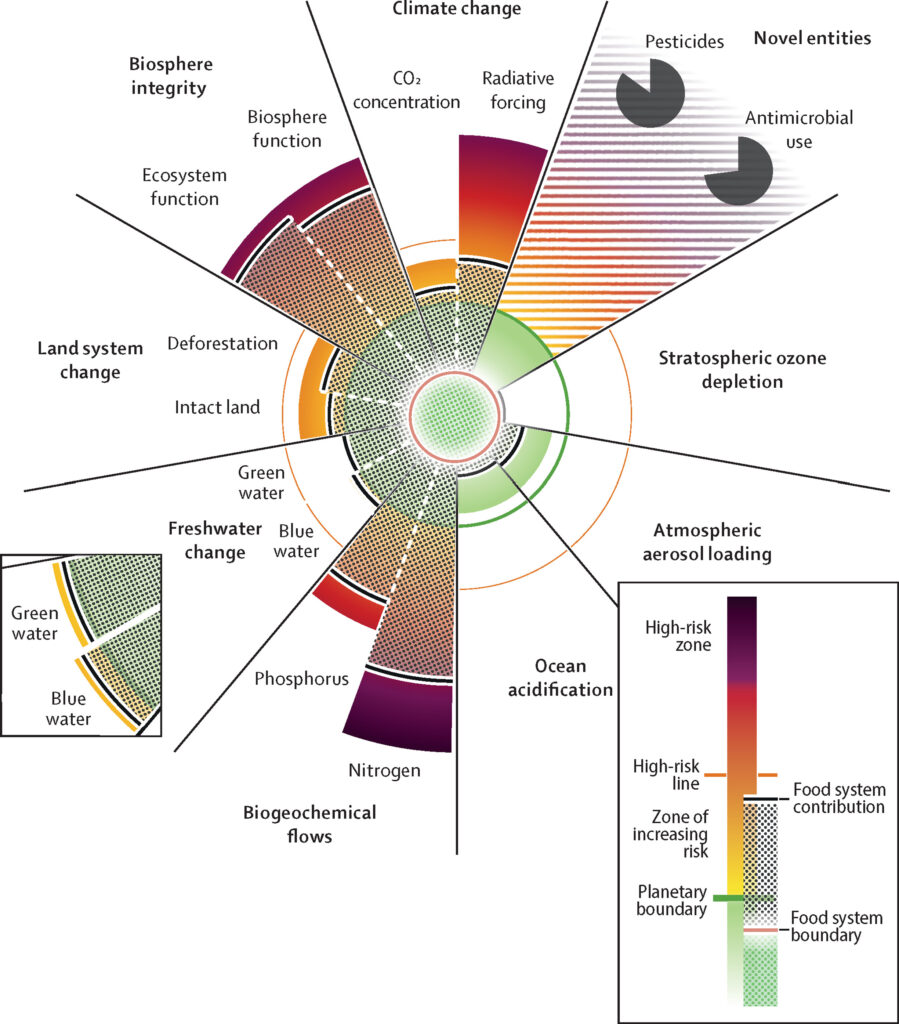

To address this gap, our team from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) has been developing new scientific tools that integrate humans and nature in a single analytical lens on up to planetary scales. Agriculture is, after all, a deeply social-ecological system: farmers learn from each other, respond to policies and markets, and work within local ecological conditions. Studying only one side of this system will always give us an incomplete picture.

Using our new modelling framework, we explore the multiple dynamics involved in transitioning to regenerative agriculture (RA). Here, we share selected insights from this research—and what they mean for a world seeking rapid, positive change.

Social norms: hidden drivers of transformation

One of the clearest findings is that social norms play a decisive role in shaping agricultural pathways. Norms can drive change—or prevent it. For example, when farmers believe that “most others farm conventionally,” they often stick with existing practices, even when alternatives might be better for their soil, yields or wellbeing. This is known as a descriptive norm, and it tends to reinforce the status quo.

Our review of current modelling approaches showed that these descriptive norms that often act as barriers to change in our farming systems are captured relatively well in current modeling approaches. Far less represented are dynamic norms—the type that signal emerging change (“more and more farmers around here are trying regenerative practices”). These norms can create positive tipping points. When enough early adopters begin experimenting with regenerative techniques, others can take notice. Perceptions shift. A new normal becomes possible.

Yet these pro-change norms are rarely included in global models. This limits our ability to understand where transformation might take off, or how policy and community support could accelerate it.

Learning matters—both social and ecological

We also examined different kinds of learning processes. Social learning, manifesting as farmer-to-farmer exchanges or local extension services, can support the spreading of regenerative practices. But social-ecological learning is just as crucial: farmers experiment, observe how their soil responds, and adjust their practices accordingly.

Our modelling suggests that when these two forms of learning interact, their effects can potentiate. Farmers not only imitate one another—they adapt practices to their specific environments, increasing long-term success.

Ecological impacts: promising, but context matters

Our results also confirm that even simple and long-established regenerative practices—such as conservation tillage—can improve soil health and sometimes even yields at the global scale. These gains accumulate gradually but meaningfully, supporting resilience under climate stress.

However, global regenerative outcomes are highly dependent on local conditions. Soil type, water availability, cultural traditions and land-tenure arrangements all shape what is possible. Because of this heterogeneity, successful regenerative transitions cannot rely on “one-size-fits-all” solutions. They must be grounded in local social and ecological realities, while supported by broader enabling policies.

Why this matters

As the EAT-Lancet report makes clear, agriculture is central to whether humanity can return to a safe operating space. But transforming agriculture is not only a technical challenge—it is a social-ecological transformation. Policies that focus solely on agronomic practices will miss the social dynamics that determine whether those practices are adopted, adapted or resisted.

By developing integrated models and tools—such as our copan:LPJmL framework and the InSEEDS World-Earth model—we aim to provide tools that help study the agriculture turnaround, identify where regenerative transitions are likely to emerge, how they spread, and what supports them.

For regenerative agriculture to flourish globally, we need a clearer understanding of the coevolution of societal and ecological dynamics that shape change. Only then can we design strategies that help farmers, communities and ecosystems thrive together.