The world needs to shift to a radically different economic model if it is to avoid stagnation and ensure prosperity for all. Businesses will ultimately benefit from this transition, but they must play an active role in system change if they are to be part of the solution, rather than part of the problem.

The world faces a long crescendo of ever worse disasters if it continues with the economic policies of the past 40 years. Decision-making-as-usual will drive up inequality and social tensions, which in turn will lead to a decline in trust, political destabilization and economic stagnation. And this will all make it increasingly difficult to take coherent long-term decisions to tackle existential threats such as global warming.

Powerful state-of-the-art computer modeling used in a two-year research collaboration for our new book Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity shows that continuing with the current system and making only incremental efforts to deal with existential crises would lead to declines in wellbeing, even in wealthy nations. In this ‘Too Little, Too Late’ scenario, global temperatures would reach 2.5C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. All societies would suffer shocks from more extreme events such as heatwaves, drought, crop failure and floods. Around two billion people would be living in areas close to the limits of human habitability.

But there is an alternative. The book, which builds on the experience from the Club of Rome’s groundbreaking 1972 report The Limits to Growth, sets out a clear pathway for a reboot of the global economic system so that it works for all people and the planet.

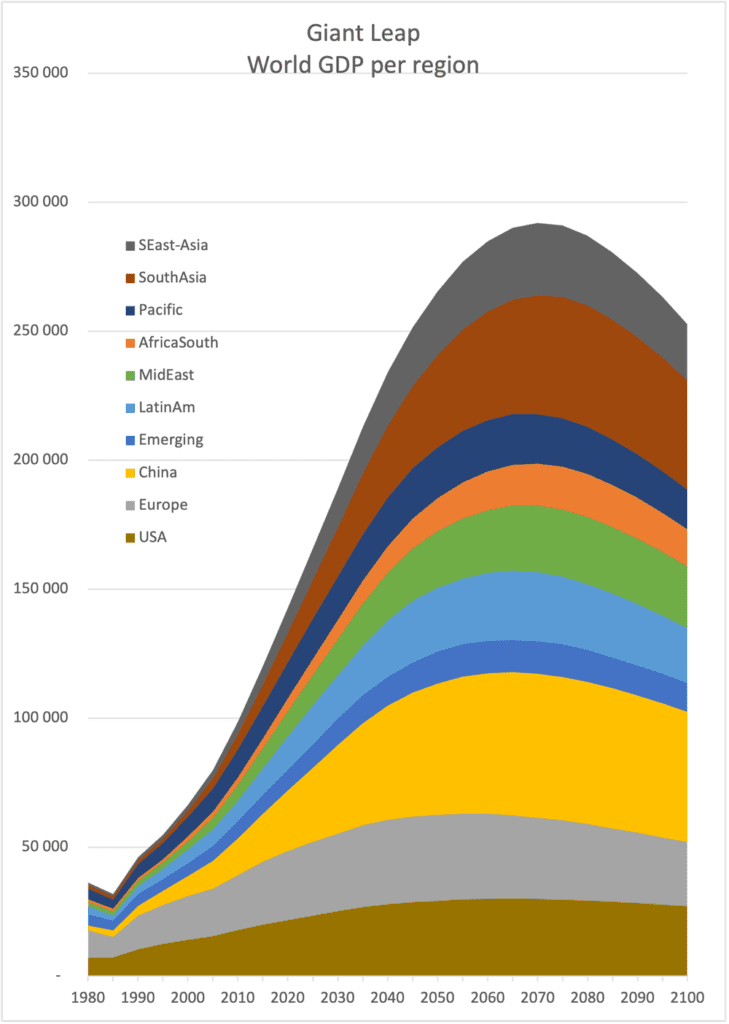

This ‘Giant Leap’ scenario entails rapid system changes or ‘turnarounds’ in five areas – poverty, inequality, female empowerment, energy and food – which societies could start implementing now.

The model indicates that this bold strategy could lead to prosperity for all on a liveable planet by 2050. It would make it possible to limit global warming to less than 2C, stabilize the world’s population at well below nine billion, reduce material use and approach an end to extreme poverty globally within this timeframe. At the same time, average income per person grows. In this scenario, average wellbeing would rise throughout the century not least also because of greater income equality and a better environment.

This would not mean an end to per capita economic growth, but an end to a myopic focus on growth at the expense of what really matters in economic policies – human wellbeing. This new direction for our economic system requires a more nuanced approach to growth. Consumption of many materials cannot keep growing, and greenhouse gas emissions need to be halved every decade. Happily, revolutions in energy, food and material flows will also drive jobs and economic growth. Low-income countries need to rapidly grow their economies.

The book outlines a simple set of policy recommendations that we assess have greatest potential to accelerate these turnarounds in each of the five areas.

To lift 3-4 billion people out of poverty, it proposes investments and debt cancellation for low-income countries to enable them to achieve annual GDP growth rates of at least 5% until GDP per capita reaches $15,000. At this level, most social sustainable development goals can be met.

To reduce inequality, it argues for increased taxes for the 10% richest in societies until they take less than 40% of national incomes. Globally, this group currently takes over 50% of national incomes, which is a recipe for deeply dysfunctional, polarized societies. The book also proposes the creation of Citizens’ Funds that would distribute common and national wealth through fee and dividend schemes.

While we recommend additional taxation to transfer wealth from corporations and capital owners to the rest of the population, this redistribution in favour of the 40% on the lowest incomes will actually be positive for businesses because inequality acts as a brake on growth. When the purchasing power of the poor goes up, so does growth, and this is good for corporate profits.

The same goes for pay. In the United States, the Palma ratio, which measures the incomes of the top 10% divided by the earnings of the bottom 40%, is around 3. In South Africa, it is 7. But research shows that if this ratio can be reduced to around 1, this leads to greater wellbeing, health and improvements in GDP growth. It improves both labour- and resource productivity, as we see already in many Scandinavian countries. A society with more tolerable levels of inequality benefits everyone, even the very rich.

To empower women by achieving full gender equity by 2050, governments should increase education access for all girls and women, and all corporations and public bodies must reach gender equality in leadership positions. Market economies that invest in gender equity and families regularly top international polls on innovation, wellbeing and happiness.

Our food systems also need to be comprehensively redesigned to create a regenerative, sustainable food system that works for all within planetary boundaries. Our current system exposes 9% of the world’s population to severe food insecurity at one extreme, while at least 8% of deaths are attributable to obesity on the other. This requires measures to reduce overconsumption and end wastefulness in food chains, more sustainable and regenerative practices in agriculture and a shift to healthier diets with less grain-fed red meat.

Finally, in energy, investments in new renewables capacity need to be tripled to more than $1trn a year as we phase out fossil-based energy systems in order to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Solutions to improve energy efficiency and halve emissions in a decade are now available, affordable and ready to scale rapidly.

Businesses have a crucial role to play in this system change. The turnarounds outlined will create vast opportunities for organizations, but they will have to adjust their strategies to take advantage. If we are to succeed in achieving growth rates of 5-7% in low-income countries, this will mean that the 4 billion people currently living on less than $4 a day will represent the world’s biggest market by 2050, so businesses need to position themselves for this shift, for example (see Figure).

In areas such as the energy transition and the overhaul of the food system and the elimination of single use plastics, businesses will have to decide if they are part of the problem or part of the solution. And if they want to be on the right side of history, they will have to decide how they can contribute to this wave of change.

This may require additional spending in the short term, but this should be regarded as investment that will boost profitability in the long term.

And it means aligning your actions with your words.

If you ask any CEO whether sustainability is important to their future business, the vast majority will respond with a resounding yes, but the numbers fall dramatically when you ask if they have integrated it into their core strategies or made the business case for sustainability projects, so there is a huge gap between companies’ words and actions in this area.

Science-based targets are therefore essential to measure performance and impact. Businesses need to be able to track their main footprints relative to their value creation and show how they are improving resource productivity and the inclusiveness of their growth. This should be the minimum for any company that wants to walk the talk on sustainability. Otherwise their glossy ESG brochures are probably just greenwashing.

First published on IMD